How adaptive management is changing international development

.@JGConline & Richard Kokeš share lessons from their #HumanLearningSystems project that aims to change ways of thinking in the Czech child protection system

Share article"We want to enable social services to provide well-targeted support at the right moment – before family crises escalate" @JGConline & Richard Kokeš

Share articleIn this piece, @JGCOnline & Richard Kokeš discuss the importance of local autonomy, system stewardship & trust in child protection

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

There is a 13-year-old boy in the Pardubice region of the Czech Republic who remains at risk today because child protection workers in his area aren’t empowered to directly intervene on his behalf. Child protection services first made contact with the family ten years ago, and while alcohol-fuelled violence is a constant presence in his home, their hands are tied: they can currently only serve as coordinators of the service network, not advocates for his protection.

Unfortunately, this boy’s situation isn’t uncommon, which is what led us to launch a Human Learning Systems (HLS) project to change ways of thinking in the Czech child protection system. The project has three teams specialising in different aspects of child protection. The first focuses on parent divorce – the most common issue faced by child protection services – the second on child safety risk evaluation, and the third on how to thrive as a child protection worker in light of the role’s inherent pressures.

In our view, child protection workers should have been able to make a direct intervention – such as conducting systemic family therapy – at the first sign of danger. Instead, they have only been able to refer the parents to numerous different services - including psychologists, marriage counsellors, and later on psychiatrists - that haven’t been connected or led to meaningful change for the family.

We want to enable social services to provide well-targeted support at the right moment – before family crises escalate.

The thesis that guides our work is that an HLS approach can enable child protection workers to change the pattern of parental conflict by building a relationship with the family and helping the boy to be safe. We want to enable social services to provide well-targeted support at the right moment – before family crises escalate.

For this project, we put together a stakeholder group that is representative of the Czech child protection system as a whole, from frontline caseworkers to Prague-based policymakers and the child protection department of the Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (MoLSA).

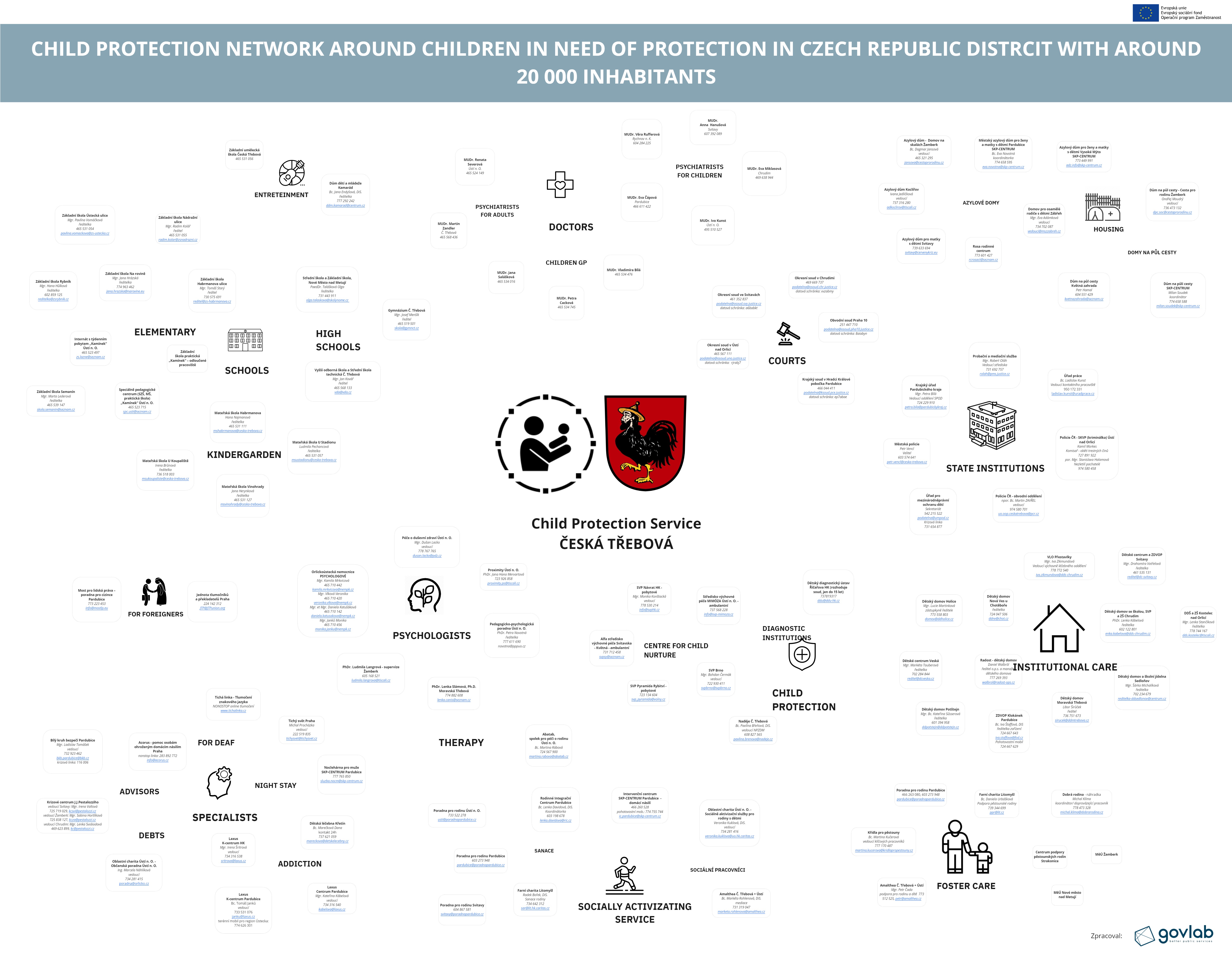

As the network diagram shows, there are numerous public agencies interacting with the Pardubice region’s child protection service. Even a small child protection team of up to 10 workers cooperates regularly with 50 to 100 different institutions, and this can make for a bewildering array of interconnections.

The importance of nurturing local autonomy

Our biggest challenge has been to make project participants the owners of the creative process. To do this, we have used HLS techniques to share learning and improve working practices, placing a premium on nurturing local autonomy. We have learned the importance of dispensing with performance objectives, outcome “management”, and other accountability systems that are set remotely by top-down management.

To begin with, we spent six months visiting the child protection teams and building trust with them, so that local staff and management were fully committed to the project. Once local teams were in a position to run experiments themselves, we followed a very deliberate strategy to build local autonomy, complemented by a mechanism to share learning with other localities.

Each of the three child protection teams has specialised in a different area and run its own experiments. In its focus on divorce, the first team’s initial deep dive was into parents’ separations and quarrels over children. We mapped the process thoroughly with the team members, both individually and collectively, analysing all the parents’ contacts with social services and other institutions, and the time and effort they consumed. The other two teams then validated these newly-developed practices in their own context as a preparatory step for scaling.

Regional teams are then involved in facilitating and amplifying this local learning process, so that an innovative practice is prepared for wider sharing across the region. We have used the sharing and critique of local proof-of-concept experiments to develop a common purpose and perspective, build competency in shared methodologies, and devise tactics to disseminate HLS thinking more widely.

We have strictly observed a dual principle of autonomy and collaboration, so that all the outputs created with local or regional teams are retained within that team – until they are ready to show them to a wider audience. Thus, all the outcomes are a product of learning-led, participative working. This helps to nurture mutual respect within and across teams, and we are confident that our approach will produce better and more sustainable results than conventional approaches to change.

Learning the art of system stewardship

The role of the system steward in HLS is to enable system actors “to connect and collaborate, so that our systems work to serve the people they are supposed to benefit”. Embedding these principles and linking “health system” practices at the local, regional and national levels is the system stewardship challenge.

The practice of system stewardship must be developed as a new leadership practice, which gradually supersedes conventional centralised control. This requires systematic and patient capacity-building, a structured method, and the development of alternative assurance processes which are optimised for learning. If not, the existing reporting and performance management routines would overwhelm the learning space.

Instead of defining the “what and how” of change, system stewards become involved in supporting the development of prototypes and testing innovative practices, while coordinating efforts to scale effective practices at a system level. We have encouraged actors across the system to share information and learn together.

Instead of defining the “what and how” of change, system stewards become involved in supporting the development of prototypes and testing innovative practices, while coordinating efforts to scale effective practices at a system level.

A powerful tool to achieve this has been to create in-depth family case studies. These provide an overview of current system reactions. With support of experts in the practice of psychology or child protection, we create an ideal, clean service route for these sample cases. This in turn leads us to a vision for future improvements. After that we prepare small experiments in which we aim to get as close to the vision as possible.

We are testing and developing this new approach in parallel with the continued use of the existing system. Leaders are therefore running three “performance management spaces” concurrently – the existing system, the emerging experimental approach, and a potential future solution. Holding this tension is a critical effort for leaders as they build their system stewardship role.

We have benefited from using tested approaches from past projects in steering participants to connect different organisations and levels horizontally and vertically across the system. Over time, the responsibility for maintaining learning processes will transition to the system stewards, as their confidence, experience and competence begin to grow.

Building the technical on a bedrock of trust

Results flow from relationships, and we have learned that normally technical disciplines need to be built on a human bedrock of trust, empathy, and collective action. We are aiming to create a “results through relationships” culture, where we recognise the importance of being human to one another.

Innovation in each locality starts with a social process of relationship-building and shared sense-making. Different teams of the same type – such as child protection teams – concentrate on their specialised learning areas, before sharing their learning through social processes to build co-ownership and relationships of mutual trust.

A central practice in building empathy between actors in the child protection system has been to adopt a key aspect of Easier Inc's change model – developing structured listening skills. Early on, it became clear that as soon as a case presented, professionals were eager to fire out solutions and ideas about what needed to be changed in the family’s situation.

The most important insight was that families were “processed” by numerous agencies in standardised patterns that did not match their particular situation or needs, and they are often mitigating the symptoms of a problem rather than the problem itself. We needed to listen to these insights and create a bespoke response for each child and family – a more humane service design.

In one example, we created a series of 32 cards describing common situations in which clients interact with child protection services, but where not everything works out ideally. This process helps families and workers not only to talk openly about information and technical topics but also to confront the more difficult emotional questions. It serves to build a deeper understanding and more empathetic relationships.

The results of the pilot will be presented to the Pardubice regional authority and MoLSA. We see the project as a proof-of-concept for a radically different setup, which draws considerable inspiration from the Dutch system. We are working on the hypothesis that the Czech child protection system is too functionally specialised, with numerous NGOs and clinics focusing on very specific problems. This leads people to see problems as purely technical ones, where the job of the system is to find out what is wrong with family and repair it.

We plan to spend around six months in the project test phase with each team. We will ensure that the teams involved have the support of psychologists to help them process the social as well as the technical aspects of the emerging changes. We aim to conduct a full service redesign, including testing, for which we will need to run three workshops of around eight to ten people. We have a psychologist and a child protection expert ready to begin the process, as soon as the pandemic allows.

It is critical to maintain this “healthy system” focus and momentum, and to build upon it. So far, we have concentrated on embedding these practices within the local and regional teams, prioritising core capabilities and the quality of interaction with families. We plan to continue to expand the experimentation model to all the local teams in the Pardubice region. In collaboration with regional and national actors, we are also developing materials – such as learning programmes and adaptable blueprints – that will allow us to extend innovation to other Czech regions.

We have already introduced HLS approaches to more MoLSA departments, and we are helping local government, the criminal justice system, charitable foundations, and other interested parties with support for tactical improvement and strategic organisational change. Going beyond the realm of child protection, we are hoping to popularise the idea in Czech public services that human learning and citizen-centred design can be better both for citizens and the public purse.

We’re exploring how Human Learning Systems can offer a complexity-friendly approach to public service delivery in line with our emerging vision for government. In this series, we highlight the stories of government changemakers who are pioneering this approach – their breakthrough moments, successes, and what they’ve learned from failure – as well as what we’re learning from them along the way.