Technology in the wrong places: a more human approach to workforce development in Kingston

.@ElenaBolbolian from @MyGlendale calls on all departments to embed #humancentered design into their activities, co-creating solutions with communities instead of creating on their behalf

Share article.@MyGlendale participated in @BloombergDotOrg's Innovation Training, helping cities adopt innovation techniques that engage residents in testing, adapting & scaling ideas w/ potential long-term impact

Share articleWhat does using human-centred design to develop a solution look like? @ElenaBolbolian says 'It did not look like the traditional approach. Instead, we went to the community first to better understand their problems.'

Share articleWe put our vision for government into practice through learning partner projects that align with our values and help reimagine government so that it works for everyone.

From March 2020 to June 2021, the City of Glendale in California participated in Bloomberg Philanthropies’ Innovation Training. Innovation Training, delivered in partnership with the Centre for Public Impact (CPI), is designed to help cities adopt cutting-edge innovation techniques that engage residents in testing, adapting, and scaling ideas with the potential for long-term impact. Through participation in Innovation Training, Glendale aimed to develop a solution for diverting and recovering edible food and, overarchingly, to embed innovation capacity across City Hall.

In Summer 2017, the City of Glendale established an innovation team and tasked me with creating efficiencies within City Hall. With this broad mandate and lack of specific priority areas, I decided to focus on identifying organizational pain points and improving City processes.

In order to bring innovation to City Hall, I first had to understand it. To speed up my efforts, I connected with the cities of Los Angeles and Long Beach, as I had come across them in my early research into local government innovation teams. By connecting with these more established innovation teams, I got a sneak peek into what to expect as I put Glendale’s team and work program in place.

One of the first innovation tools I identified was human-centered design, an approach to creating a program, policy or service that is tailored to the needs of the person who will use or be impacted by it. Learning about human-centered design fundamentally shifted how I thought about public policy. As a City Hall lifer, I routinely thought about approaching policy or programs from the standpoint of City Hall, but human-centered design was something new as it centered residents. With this shift in mindset, and understanding of the value it could bring to government service, I was bursting at the seams to spread this knowledge to as many staffers as possible.

Learning about human-centered design fundamentally shifted how I thought about public policy. As a City Hall lifer, I routinely thought about approaching policy or programs from the standpoint of City Hall, but human-centered design was something new as it centered residents.

In Fall 2017, my team sought to supercharge our innovation capacity by becoming involved in a network of global innovators challenging the status quo at City Halls through participation in the Mayors Challenge. The Mayors Challenge is a Bloomberg Philanthropies competition designed to spark innovative, replicable ideas for improving cities, and the lives of people living in them, by encouraging leaders to think boldly and creatively on how to confront their most difficult challenges.

Our team applied to the competition, but was not selected to advance to the testing phase. In the spirit of innovation, we treated this as a fail forward moment. Even though we did not move forward in the competition, we were still able to learn from the ideas submitted and tested by the other cities. We continued to grow our innovation capacity and, two years later, we received another opportunity to boost our efforts when Glendale was selected as one of 12 cities in North America to receive free Innovation Training from Bloomberg Philanthropies.

In order to maximize our participation in the training program, we wanted to apply the training techniques to help solve a current challenge at City Hall. To identify our focus, we sourced challenge ideas from City staff. We received numerous ideas ranging from improving the permit counter to modernizing recruitment strategies to developing a better system for records management. In the end, we settled on the challenge of organics recycling and development of a food recovery program, a big component of California Senate Bill 1383, a mandate to slash the amount of organic waste going to landfills. This challenge rose to the top because of the mandated deadlines for cities to develop such programs. Of the multiple provisions of SB 1383, the team chose to focus on edible food recovery because it is a new requirement for municipalities, thus unchartered territory. Our goal was to use human-centered design to develop a solution to better connect recovered edible food to individuals facing food insecurity.

Absent Innovation Training and the new human-centered design method, the traditional approach to coming up with solutions would involve staff members from the recycling office and other administrators in the Public Works department. They would sit around a table and try to come up with solutions without first engaging stakeholders. In general, stakeholder engagement comes after City Hall has developed a solution.

Before we could get to learn from the challenges of our stakeholders, our team faced a challenge of our own. The Innovation Training bootcamp took place one week before City leadership was forced to close City Hall and send staff home to comply with shelter in place orders due to COVID-19. The program was paused for a few months while Bloomberg Philanthropies and CPI pivoted and re-launched the program in a virtual format. Our team was very excited following the bootcamp experience and learning about prototyping; we couldn’t wait to continue with the training. We were disappointed about the program being paused but remained hopeful that it could continue at some point in the future.

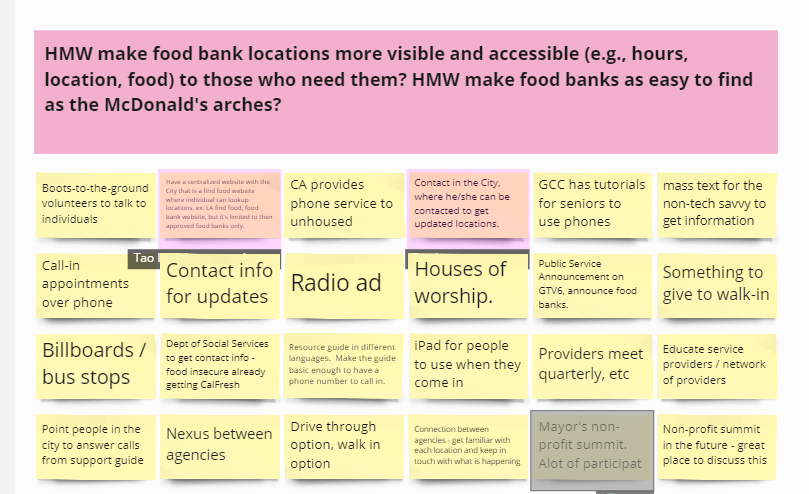

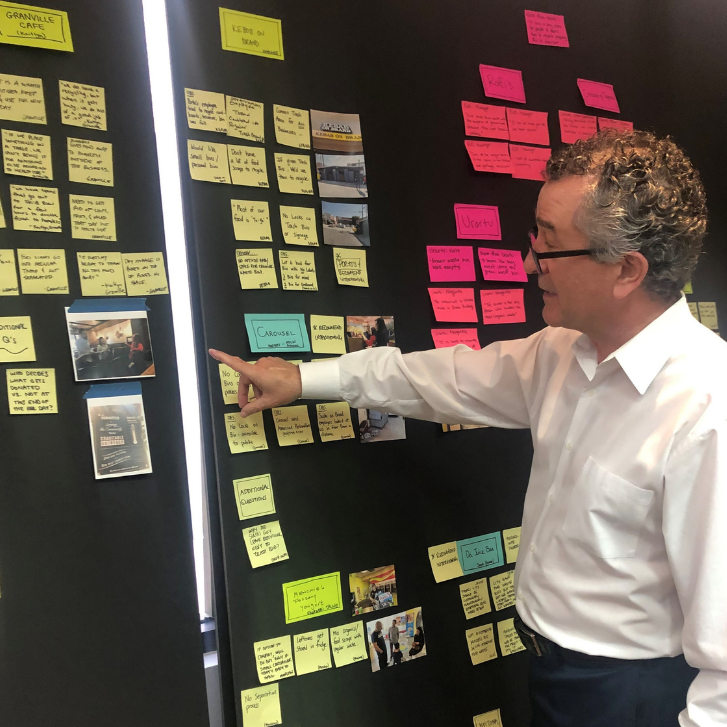

When the program resumed, our team was happy to continue but now had to adapt and learn how to interact with a new digital whiteboard and virtual formats. The early meetings proved challenging as team members struggled with the mute button and putting virtual post it notes on the digital board. As time went on, we became more comfortable with our new reality. Going through this experience strengthened our team’s dexterity. Having adjusted to our new virtual training board, we set our sights on directly engaging with the community.

Miro Digital Board

Miro Digital Board

So, what did using human-centered design to develop a solution look like? It did not look like the traditional approach, where City Hall starts brainstorming solutions and then goes out to the community for feedback. Instead, we went to the community first to better understand their problems. We worked hand-in-(virtual)-hand with stakeholders at every step of the way.

We interviewed 67 stakeholders and completed 21 in-person observations, with face masks and appropriate physical distancing. We focused on three distinct groups: 1) food distributors, 2) food establishments, and 3) food insecure individuals. This unique human-centered design approach empowered our team to learn firsthand the challenges faced by the various stakeholder groups. The approach was different than traditional solution development because it allowed us to directly learn from residents versus thinking on their behalf from behind a desk at City Hall.

As a result of these interviews, we identified ten ideas ranging from easy and practical, such as creating a map with food locations, to bold and challenging, such as partnerships with ride sharing companies to pick up and deliver food. From these ten ideas, our team decided to prototype two of them, a food court and food mobile concepts. Our first prototype was developing a centralized food court, where local restaurants would drop off their excess food and anyone would be able to pick it up. Our second prototype was a food mobile, where we envisioned an electric truck that collects recoverable food from local businesses and restaurants and cruises the streets of the City like ice cream trucks to donate food.

City Hall is currently in the process of bringing on board a dedicated consultant to work with our team to continue these initiatives and implement one of these ideas.

This unique human-centered design approach empowered our team to learn firsthand the challenges faced by the various stakeholder groups. The approach was different than traditional solution development because it allowed us to directly learn from residents versus thinking on their behalf from behind a desk at City Hall.

Beyond the direct scope of our Innovation Training, our experience also catalyzed a spirit of innovation across City Hall. When thinking about how to assemble our team, we put out a citywide call and received over 40 applications. With the citywide call, I set out to create excitement around this unique training opportunity. I was looking for staff who were eager and willing to participate in order to learn something brand new. I did not want department directors to nominate staff for this training, the traditional approach utilized with professional development courses; instead I was looking for staff who wanted to be a part of this training versus feeling obligated to participate.

Ultimately, we selected 12 team members, who represented 7 City departments, including Community Development, Water & Power, City Attorney’s Office, City Manager’s Office, Public Works, Information Technology and Innovation Department. A benefit of having a diverse group is that they consider the problem from very different angles. For example, our GIS Manager is looking at the problem from the perspective of geography and mapping while our City Attorney representative brings a risk management approach.

I view this team as City Hall Innovation Ambassadors who will be called upon to apply the learnings from the Innovation Training to their individual departments. Helping spread innovation across City Hall is one of my priorities given the small makeup of our innovation office.

In the few short months since we finished Innovation Training, we have seen the seeds planted by our Ambassadors begin to take root. Increasingly staffers are seeing real benefits from an approach that puts residents at the center. A Civil Engineer wants to revise the public noticing process on engineering projects to engage stakeholders earlier on in the design process. An attorney wants to apply human-centered design to the City’s plan to add electric vehicle charging stations. In the Innovation Office, we have utilized human-centered design to develop recruitment websites for our public safety departments by eliminating bureaucratic text and replacing it with more modern and navigable elements.

As we look towards Glendale’s future, I am hopeful that we can engage residents and stakeholders earlier on in the process. I want all departments to embed human-centered design into their activities. In this way, we co-create solutions with the community instead of creating on their behalf.

Elena is speaking at League of California Cities' Annual Conference and Expo. Join her session "Human-Centered Design and Why My City Should Care About It" on September 22 at 3:45-5PM.